@ Cinéma du Parc

lundi, Monday le 26 octobre6 p.m./ 1800 h

(English text follows...)

Devenir adulte n’est jamais simple, mais nous finissons quand même par passer au travers de la puberté, tôt ou tard, d’une façon ou d’une autre. Pour le meilleur et pour le pire.

Les films qui parlent du phénomène du passage à l’âge adulte viennent nous chercher en ce qu’ils nous rappellent nos plus doux-amers souvenirs. Ils sont une vibrante nostalgie de l’époque où nous avons appris nos leçons de vie parfois de façon brutale. On se souvient du temps où…mais oui, on revit notre propre évolution – la période de la crise d’adolescence où nous passions de mômes capricieux à de gentils adultes. Ayant tous passé par là, nous sourions à l’évocation de notre propre période d’adolescence. Ces films ravivent notre mémoire, faisant reluire nos éclats d’étourderie. On se languit et se souvient du « doux temps » de notre innocente jeunesse..

Les Beaux Gosses (French Kissers), film en compétition officielle, ce printemps 2009, dans le cadre de la Quinzaine des Réalisateurs au Festival de Cannes. Cinémagique a le plaisir et l’honneur de vous le présenter, lundi, le 26 octobre, au Cinéma du Parc. Une comédie croustillante teintée de gags grivois à la Mack Sennett, roi de la comédie et du cinéma burlesque avec des blagues frôlant parfois le ridicule.

Les histoires traitant du passage à l’âge adulte sont à tout jamais rattachées à une époque et à un endroit précis. Des souvenirs personnels à peine déguisés du réalisateur lui-même. Les Beaux Gosses explore cette jungle impénétrable de ce qu’est un adolescent dans une petite ville bretonne en 2008. Et pourtant, quoique ces ados Beaux Gosses 2008 soient tout aussi différents de ceux dans Blackboard Jungle (1955), malgré qu’ils soient au temps de l’informatique, malgré une vie de médiation depuis l’enfance, malgré leur génération et culture MTV, malgré qu’ils soient conscients du virus du sida, malgré une omniprésente pornographie, ces ados nous arrivent comme d’innocents personnages tout naïfs tels que nous l’étions il a très longtemps déjà sur une planète très lointaine.

Hervé (qui ressemble quelque peu à Michael Sera) est un vulgaire petit connard qui veut séduire, qui se masturbe et qui rêve à ses fantasmes. Son univers d’aujourd’hui – comme le nôtre jadis – conspire contre lui, l’amène sur des sentiers dangereux, l’incite à cesser de réfléchir en enfant, à repenser son rôle d’adulte, à surmonter d’innombrables obstacles tels qu’aliénation, opportunités illimitées, la mort, les drogues, l’existentialisme, l’aventure, confusion, flirt, commérages, l’incertitude, l’irresponsabilité parentale, l’insécurité, l’instabilité, libido, mensonges, faible amour-propre, musique, frivolités amoureuses, discours philosophiques, précocité, psychisme, sauvagerie, concentration sur soi, sexe, sexe et re-sexe…Complétez ce programme et vous voilà diplômé adulte !

Bref, les films sur le passage à l’âge adulte sont de nature embêtante. En voici quelques paramètres :

Les films sur le passage à l’âge adulte ne se passent pas seulement avec des gars. Rappelez-vous les filles merveilleuses dans ce type de films : Juno; Girl Interrupted; Bend It Like Beckham; To Kill A Mockingbird; Whale Rider; 16 Candles; Rabbit Proof Fence; Celui de Peter Jackson, Heavenly Creatures ainsi que (dois-je le mentionner?) Lolita. Ces films sont aussi de style très Canadien/Québécois. On n’a qu’à penser à : J’ai tué ma mère; Les Bons Débarras; celui de John N. Smith, New Waterford Girls; My American Cousin de Sandy Wilson; Duddy Kravitz (Richard Dreyfus est venu à Montréal à la suite de American Graffiti de Georges Lucas).

On découvre d’excellents nouveaux réalisateurs de films traitant de ce même sujet : Truffaut avec (Les Mistons, Les 400 Coups); Fellini (I Vitelloni, et puis a suivi Amarcord); Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso), Francis Ford Coppola (You’re A Big Boy Now); Peter Bogdanovich (Last Picture Show). Et ceux du réalisateur John Hughes : (Breakfast Club, Ferrie Bueller’s Day Off, Sixteen Candles, Pretty in Pink); Soderbergh (Sex, Lies and Vidotapes); L’acteur et bédéiste Riad Sattouf, auteur de plusieurs fils de comédie, est le réalisateur et co-scénariste de cette comédie tout comme s’il l’avait extirpée tout droit de ses bandes dessinées.

Venez et préparez-vous à bien rigoler !

Devenir adulte n’est jamais simple, mais nous finissons quand même par passer au travers de la puberté, tôt ou tard, d’une façon ou d’une autre. Pour le meilleur et pour le pire.

Les films qui parlent du phénomène du passage à l’âge adulte viennent nous chercher en ce qu’ils nous rappellent nos plus doux-amers souvenirs. Ils sont une vibrante nostalgie de l’époque où nous avons appris nos leçons de vie parfois de façon brutale. On se souvient du temps où…mais oui, on revit notre propre évolution – la période de la crise d’adolescence où nous passions de mômes capricieux à de gentils adultes. Ayant tous passé par là, nous sourions à l’évocation de notre propre période d’adolescence. Ces films ravivent notre mémoire, faisant reluire nos éclats d’étourderie. On se languit et se souvient du « doux temps » de notre innocente jeunesse..

Les Beaux Gosses (French Kissers), film en compétition officielle, ce printemps 2009, dans le cadre de la Quinzaine des Réalisateurs au Festival de Cannes. Cinémagique a le plaisir et l’honneur de vous le présenter, lundi, le 26 octobre, au Cinéma du Parc. Une comédie croustillante teintée de gags grivois à la Mack Sennett, roi de la comédie et du cinéma burlesque avec des blagues frôlant parfois le ridicule.

Les histoires traitant du passage à l’âge adulte sont à tout jamais rattachées à une époque et à un endroit précis. Des souvenirs personnels à peine déguisés du réalisateur lui-même. Les Beaux Gosses explore cette jungle impénétrable de ce qu’est un adolescent dans une petite ville bretonne en 2008. Et pourtant, quoique ces ados Beaux Gosses 2008 soient tout aussi différents de ceux dans Blackboard Jungle (1955), malgré qu’ils soient au temps de l’informatique, malgré une vie de médiation depuis l’enfance, malgré leur génération et culture MTV, malgré qu’ils soient conscients du virus du sida, malgré une omniprésente pornographie, ces ados nous arrivent comme d’innocents personnages tout naïfs tels que nous l’étions il a très longtemps déjà sur une planète très lointaine.

Hervé (qui ressemble quelque peu à Michael Sera) est un vulgaire petit connard qui veut séduire, qui se masturbe et qui rêve à ses fantasmes. Son univers d’aujourd’hui – comme le nôtre jadis – conspire contre lui, l’amène sur des sentiers dangereux, l’incite à cesser de réfléchir en enfant, à repenser son rôle d’adulte, à surmonter d’innombrables obstacles tels qu’aliénation, opportunités illimitées, la mort, les drogues, l’existentialisme, l’aventure, confusion, flirt, commérages, l’incertitude, l’irresponsabilité parentale, l’insécurité, l’instabilité, libido, mensonges, faible amour-propre, musique, frivolités amoureuses, discours philosophiques, précocité, psychisme, sauvagerie, concentration sur soi, sexe, sexe et re-sexe…Complétez ce programme et vous voilà diplômé adulte !

Bref, les films sur le passage à l’âge adulte sont de nature embêtante. En voici quelques paramètres :

- Pas de romans feuilletons à l’eau de rose.

- Sans banalités, sans soucis d’idéal, et sans fausses émotions.

- Sans exploitation ni lascivité.

- Le résumé d’une génération. Avec ses particularités tout en étant de portée universelle.

Les films sur le passage à l’âge adulte ne se passent pas seulement avec des gars. Rappelez-vous les filles merveilleuses dans ce type de films : Juno; Girl Interrupted; Bend It Like Beckham; To Kill A Mockingbird; Whale Rider; 16 Candles; Rabbit Proof Fence; Celui de Peter Jackson, Heavenly Creatures ainsi que (dois-je le mentionner?) Lolita. Ces films sont aussi de style très Canadien/Québécois. On n’a qu’à penser à : J’ai tué ma mère; Les Bons Débarras; celui de John N. Smith, New Waterford Girls; My American Cousin de Sandy Wilson; Duddy Kravitz (Richard Dreyfus est venu à Montréal à la suite de American Graffiti de Georges Lucas).

On découvre d’excellents nouveaux réalisateurs de films traitant de ce même sujet : Truffaut avec (Les Mistons, Les 400 Coups); Fellini (I Vitelloni, et puis a suivi Amarcord); Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso), Francis Ford Coppola (You’re A Big Boy Now); Peter Bogdanovich (Last Picture Show). Et ceux du réalisateur John Hughes : (Breakfast Club, Ferrie Bueller’s Day Off, Sixteen Candles, Pretty in Pink); Soderbergh (Sex, Lies and Vidotapes); L’acteur et bédéiste Riad Sattouf, auteur de plusieurs fils de comédie, est le réalisateur et co-scénariste de cette comédie tout comme s’il l’avait extirpée tout droit de ses bandes dessinées.

Venez et préparez-vous à bien rigoler !

****

On Monday October 26th, Cinémagique is delighted to be showing you Les Beaux Gosses (French Kissers) at the Cinema du Parc. It's a raunchy sex comedy, abounding in ribald humour, Mack Sennett slapstick and bad taste gags. Director Riad Sattouf (who grew up as a teen in Brittany) explores the ever impenetrable secret teen jungle of provincial Brittany. Author/artist of prodigiously funny adult comic books (La vie secrète des jeunes), Sattouf co-wrote this notable first movie as though he lifted his script right out of his comicbook panels.

On Monday October 26th, Cinémagique is delighted to be showing you Les Beaux Gosses (French Kissers) at the Cinema du Parc. It's a raunchy sex comedy, abounding in ribald humour, Mack Sennett slapstick and bad taste gags. Director Riad Sattouf (who grew up as a teen in Brittany) explores the ever impenetrable secret teen jungle of provincial Brittany. Author/artist of prodigiously funny adult comic books (La vie secrète des jeunes), Sattouf co-wrote this notable first movie as though he lifted his script right out of his comicbook panels.Growing up is never easy. We all bumble though pubescence, sooner or later, one way or another. And for better or worse.

Which mebbe explains why coming-of-age movies are our most beloved (IMDb lists 2110 titles), our most bittersweet of genres - they're our instant nostalgia back to that time when, our being teens on the cusp of maturity, we first learned our own cruel life lessons. Ah, yes! We watch and remember our own transition - brat adolescent to emerging adult - our never having a clue what was going down at the time. So, having been there, done that, we smile. Coming-of-age movies are our memory prods, buffing shiny our dross of forgetfulness. And we still pine and probe after that ''simpler time'' of our own long ago innocence.

While these Beaux Gosses 2008 ados are as different from the teens in Blackboard Jungle (1955) - despite their computerese, despite their mediated life from infancy, despite their MTV explicitness, despite their AIDS-awareness, despite their ubiquitous pornography - they come across as sweet innocent naifs as we remember ourselves to have been long long ago. Hervé's a fantasizing, masturbating wiseass charmer (with a passing resemblance to Michael Sera). His world now - as ours then - conspires against him at every turn, makes him navigate perilous passages, forces him to give up thinking like a kid, begin auditioning for his role as adult, overcome a veritable A to Z of hurdles: alienation, boundless possibility, confusion, death, drugs, existentialism, flings, flirtations, gossip, gropings, irresponsible parents, insecurities, instability, libido, lies, low self-esteem, music, petting, philosophical rambles, precocity, psyche, savagery, self-focus, sex, sex, sex, and sex, Get through and you graduate into adulthood.

Iconic coming-of-age movies are a tricky genre to execute, forever locked in their own time-and-place capsule: coded, personal, barely disguised remembrances of a filmmaker's own adolescence. Consider the genre parameters:

- No soap opera.

- No banality, no high-mindedness, nor sentimentality.

- No exploitation nor prurience.

- A summation of a generation. Particular and yet universal.

Because they're so hard to pull off, we often first spot the next breakthrough director in his coming-of-age movie. Consider: Truffaut (Les Mistons, Les 400 Coups); Fellini (I Vitelloni, and then later, Amarcord); Giuseppe Tornatore (Cinema Paradiso), Francis Ford Coppola (You're A Big Boy Now); Peter Bogdanovich (Last Picture Show). Director John Hughes made a career of his adolescence:(Breakfast Club, Ferrie Bueller's Day Off, Sixteen Candles, Pretty in Pink); Steven Soderbergh (Sex, Lies and Videotapes).

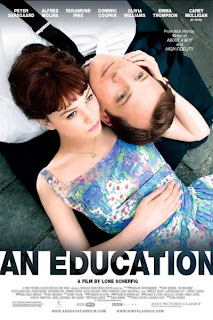

Coming of age movies are not only boy genres. Remember all the spectacular girls we saw come of age on film: Juno; Girl Interrupted; Bend It Like Beckham; To Kill A Mockingbird; Whale Rider; 16 Candles; Rabbit Proof Fence; Peter Jackson's Heavenly Creatures, An Education (last week) and (dare I mention it?), Lolita. Coming of age is also a very Canadian/Québecois subset: J'ai tué ma mère, Les Bons Débarras; John N. Smith's delicious New Waterford Girls; Sandy Wilson's My American Cousin; Duddy Kravitz (Richard Dreyfus came to Montreal right off the set of George Lucas' American Grafitti).

So come, prepared to laugh. At these kids. At what we once were..

peter

****